The shadowy Patagonian bureaucrat sitting opposite me gave up trying to scoop the pineapple sorbet out of his terremoto cocktail with a straw and pushed the glass aside.

“There’s a berry from my region, which obliges you to return if you eat one.”

That was the first moment of “how did I get here?”, a refrain that, ten thousand kilometres away from Europe, would become common as the year passed by.

Ending up in Santiago was simple enough. I had started the semester at Universidad Católica and with it, the search for Chileans to interview for a linguistics-based YARP about the prevalence of palatal fricatives, a sound like the German -ich that only appears in Chilean Spanish.

That first Chilean winter, the moments that stood out were the little ones; the dusting of snow on the mountains that surround the city, the smell of oil from the carts selling fried sopaipillas (pumpkin doughy things) outside university, the crush in the metro at 8.30am. The sing-song accent, the old, cold colonial houses. Three weeks in, I lived through my first earthquake. I thought it had just been a particularly strong pisco sour, until my Chilean housemate started answering the phone to his concerned family members.

Fast forward a few months and to leaving my last informant’s office in La Moneda. Finishing the first stage of the YARP meant I could take a short break from “la pega” – “work” in Chilean – of interviewing people, harvesting their speech samples and turning them into images.

Perhaps it was the sense of finally finishing interviews and not having to strap any more microphones to any more long-suffering good-natured Santiaguinos, but the sunset over the city was especially beautiful that night. Celebrating, I made friends with a bilingual Chilean comedian at the same bar I had met most of my participants.

One week remained before I had to give the recording equipment back to the staff at UC. I did what any sensible person would do in the situation: I fled the rapidly increasing heat of the Santiago summer and went south.

The 12th Region of Chile feels disconnected from the rest of the country, and with good reason: the roads connected to it pass through Argentina, rather than Chile, and the most direct way in is by three-hour flight to Punta Arenas from Santiago. A giant ice barrier protects Magallanes y la Antártica Chilena from the microbes that live further north. They have their own regional flag, and drink yerba mate tea out of a special gourd with a metal straw, like the Argentines do.

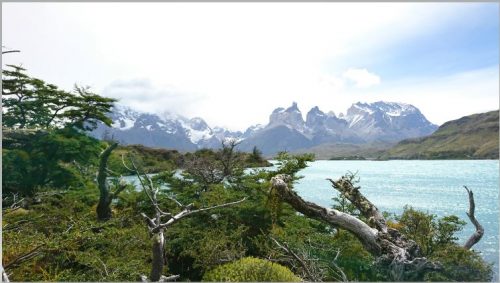

The first stage of this spontaneous Patagonia trip ™ naturally involved a trip to Parque Nacional Torres del Paine, located a few hours away from the nearest town, Puerto Natales.

At the edge of this magnificent lake, our guide picked a dusty handful of these berries from the bush: they were calafates, native to the region.

Once we had eaten them, she informed us that if a person eats a calafate berry, in local legend, they are spiritually committed to return to the region – almost the exact same words as those recited by that shady Patagonian bureaucrat in the bar. Slightly more worryingly, no records exist as to whether somebody has not returned to the region after eating one of these berries and lived.

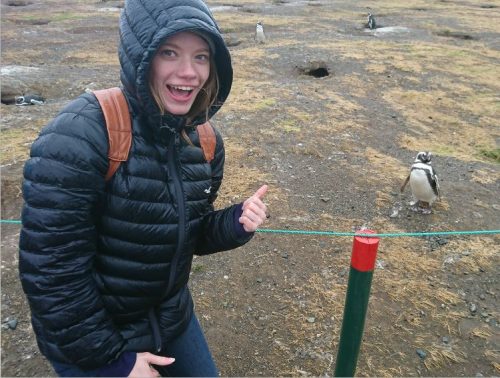

The next day I got the early morning bus from Puerto Natales back to Punta Arenas and spent the day projecting unrequited ludicrous enthusiasm onto multiple indifferent penguins in the Isla Magdalena penguin preserve, two hours ferry ride away down the Strait of Magallanes.

I had expected Punta Arenas to be hostile and isolated, but it was a busy and golden little city, strangely reminiscent of northern Europe (Helsinki sprang to mind.)

I had missed calls when the plane touched down. It was the same comedian I had met in the bar that day I finished interviewing my last informant. His friend was hosting a public speaking event in a few weeks’ time, but needed several more people to participate. Would I mind?

That was how I ended up in a theatre in Bellavista, anxiously twisting a microphone cord, about to launch a hastily-written script at an audience I didn’t know.

“What are the standout moments from Santiago?” I asked the blue-lit faces below the stage. “The silhouette of the radio towers on Cerro San Cristóbal? The national fascination with the avocado? The slightly viscous quality of a half-melted terremoto?”

And then, something miraculous happened.

The audience laughed.

Not just a polite chuckle, either, an actual laugh. This happened twice, three, four times. The next month is a blur: I joined a bilingual group of semi-professional stand up comedians and started going to their meetings.

Subsequently, tenuously linked to the story of the calafate in Patagonia, is that I did manage to scrape together a fledgling reputation as a stand-up comedian in Santiago, propelled in no small part by jokes about unbreakable berry-based contracts. In fact, this is one of my favourite moments of the entire year: making the notoriously difficult crowd applaud at the intimidating and atmospheric Comedy Restobar in the Barrio Italia neighbourhood, just outside the city centre.

In retrospect, would I recommend studying abroad? Of course! At PUC I had the opportunity to work for an incredibly intelligent and driven team in a Spanish-speaking linguistics lab. Would I recommend going to Chile? Absolutely! The landscapes are amazing, the dialect defies investigation and the Chileans, for the most part, are delightful. Would I recommend the calafates? Honestly, they were bitter and full of seeds. But they did provide the impetus for a fun piece of observational comedy. Plus, Patagonia is stunning. I’ll probably go back.